For a locked-down nation in desperate need of good news, the latest information on England’s badger cull brings little respite. Bovine tuberculosis (TB) is a major problem for farming and, while most cattle herds are infected by other cattle, a small proportion are infected by badgers. The government’s response has been a mass slaughter of badgers, pursued by farming groups with a scale and energy that would make you think badgers were invading aliens, rather than a legally protected native species with an important role in Britain’s depauperate ecosystems.

The annual badger cull statistics are usually announced just before Christmas, but the 2019 figures were delayed by a general election and released, without fanfare, last week. They make grim reading for anyone who values wildlife.

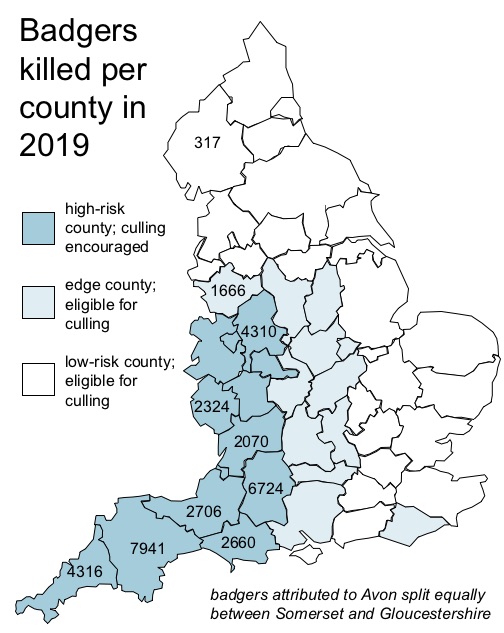

In 2019’s seven-week culling season, 35,034 badgers were killed under licence in England. To put that number in perspective, if the 2019 cull had been spread evenly across the whole year, there would have been a badger shot every 15 minutes. During the seven weeks of culling, while you notched up your eight hours’ sleep a night, a badger was being shot every 40 seconds. If at the end of the slaughter, you had laid all those dead badgers end to end, the line would have meandered down the road from Defra headquarters in Westminster, all the way to Heathrow airport. Add in those killed since the culls started in 2013, and you could have lined them up from London to Brighton.

Most of the badgers killed in 2019 were shot using a method condemned as inhumane by the British Veterinary Association. Monitoring of culling practices by Natural England found that, when 132 badgers were shot and killed, six were wounded and not retrieved. Scaling up from these observations suggests that the 24,645 badgers reported as shot and killed would conceal a hidden 1,120 wounded and suffering.

It’s a lot of dead badgers, but it’s still fewer than the government intended to kill. The minimum target set before the culls started was 37,482 – the maximum a massive 64,400 (London to Whipsnade, if you’re wondering). Every year the government sets targets for the number of badgers that each licensee must kill. Every year, it adjusts those targets during the culls so that they better match the numbers actually killed. The policy states that culls must reduce badger numbers by at least 70%, but neither farmers nor government have any idea how many badgers there are to begin with.

2019 was the first year when the number of badgers killed for TB control in England (35,034) exceeded the number of cattle killed for the same reason (31,102). That’s a lot of dead cattle, but it’s only a tiny fraction of the 1.9 million cattle slaughtered for food in England and Wales in 2019. And remember, all the cattle slaughtered for TB control are known or suspected to be infected with TB. Most of the badgers are not.

A particularly stark example comes from Cumbria, a county which mostly experiences low cattle TB risks, but developed a local pocket of infection following the import of infected cattle from Northern Ireland. The infection spread to badgers, and in 2019 Cumbria was the only low risk county to host a badger cull. Little information has been made public about this cull, which is not subjected to the requirements about cull zone size or target numbers to kill which apply to other areas. But in 2019, of 317 badgers killed, only 22 were killed inside the minimum area where cattle were affected by TB. These figures suggest that the area where cattle are affected by TB (which is not made public) must be much smaller than the area of the cull. Within this TB-affected area, two of 20 badgers TB-tested were infected, while a further 289 badgers from the surrounding land tested negative.

Is such wholesale slaughter of native wildlife worth it? The government’s analysis of the costs and benefits of culling values badgers only in terms of the amount it costs to kill them. But there’s an alternative which need cost no badger lives at all: badger vaccination is a promising tool for TB management, which is cheaper than culling, more humane, and probably more effective in the long term.

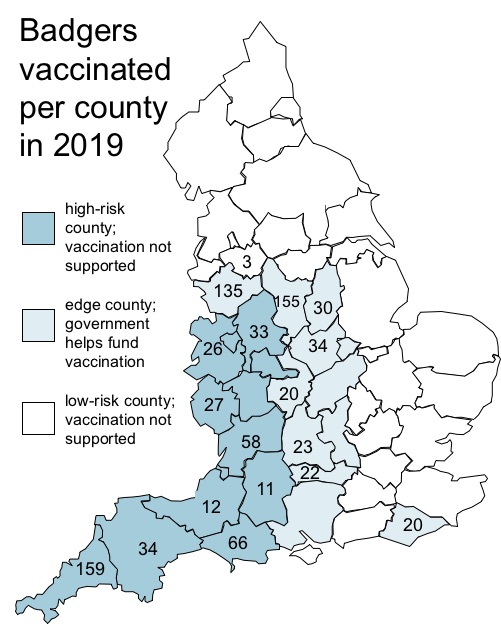

The government recently announced a plan to transition from badger culling to badger vaccination, but in 2019 the scale of culling dwarfed vaccination. Badger culling was licensed over 21,321 sq km, an area roughly the size of Israel, while vaccination was licensed over just 228 sq km. The number of badgers vaccinated (890) was just 2.5% of the number culled.

Still, there are promising signs for badger vaccination. The government helps to fund badger vaccination in the “edge” area of England, but it provides no such support in the parts of England where cattle TB risk is higher and culling is vigorously pursued. Nevertheless, in 2019 there were slightly more badgers vaccinated in the High Risk Area (448) than in the Edge (439), suggesting that wildlife groups are pursuing badger vaccination despite receiving no government help. Badger vaccination took place in almost every high-risk county, showing that a small but important core group of licensed vaccinators are scattered through the country, and may be able to help the government ramp up vaccination in the coming years.

What is needed now is for these vaccinators to mobilise. A shortage of trained vaccinators limits the phase-out of culling, so those who are already trained have an important part to play. They need to reach out locally to farmers and vets, to make it clear that they are there to help. They need to put aside past disagreements about culling, and commit to working together. They should make themselves known to local wildlife groups, who may be keen to help deliver vaccination. The badger cull is an embarrassment for a nation which claims to show “global leadership in protecting wildlife in its natural environment“, but it’s not irreversible. There’s a long, long way to go to reach a shared understanding between scientists, farmers, veterinarians, and conservationists of the role that badgers play in TB transmission, and the need (or otherwise) to kill them. Government plans still include the option to cull. But vaccinators from Land’s End to the Peak District are starting to normalise vaccination. Trapping in former cull zones will be hard and unrewarding at first, but new cubs will be born and, over time, the badgers will come back.

An excellent article showing the true picture of how wildlife is being systematically destroyed throughout England, by people claiming to lead the world in protecting it. They epitomize the definition of hypocrisy.

Excellent summary but why is the cull continuing when it is clear that killing badgers is not a solution. Who is driving this policy? Certainly not scientists. There has been no political will to produce a cattle vaccine and diva test which were going to be ready by 2014. There are 1.7 million cattle movements per year. Farmers are spreading bTB around the UK. The Cumbria outbreak was caused by a single bull imported from northern Ireland. So we are killing the badgers in Cumbria. Of the 313 badgers killed in Cumbria in 2018 only 3 had bTB which they caught from cows. We have killed over 110,000 badgers because the govt is too scared about losing farmers’ votes. This has to be stop NOW.